AI for a multiplayer snake game

03 Jan 2017

I worked on this project with Sebastien Levy and Felix Crevier for Stanford’s CS221 course Artificial Intelligence: Principles and Techniques. Our goal was to implement AI-based strategies for a tailor-made game of multiplayer snake, inspired by the popular online game slither.io.

Overview

In short, multiple snakes move on a 2D grid on which candies randomly appear, and grow by one cell every second candy eaten. Snakes die when their heads bump into borders or other snakes. This adds an interesting complexity to the classic snake game, as snakes can try to make others collide with them.

The main motivation behind this project was to assess the relative performance of adversarial strategies versus reinforcement learning and compare snake behaviors inherent to each. In addition, this game setting comprises a number of challenges, such as simultaneous player actions, multiple opponents and large state spaces. Finally, there is no single conspicuous objective, thus making it difficult to predict the opponents’ best moves in search trees and makes RL policies very dependent on the strategies used for training.

Our full report can be found here, and all our code is available on GitHub. I’ve mostly worked on the reinforcement learning part, so that’s what I will focus on in this post. In addition, I’ve continued working on this project since we handed out the report so not everything I’m presenting here was detailed in there.

RL agent is in purple

Reinforcement Learning approach

We implemented the RL agent through Q-learning with global function approximation. Precisely, the goal is to learn a function Q(s,a) which measures the expected future rewards when taking action a from state s. Once this is learned, we can compute the optimal strategy by choosing the action that maximizes Q for the current state.

We used very simple (yet quite powerful) features to describe the state-action pair. The idea is to start from the state s and make the agent move with action a (but everything else is fixed), then mentally rotate the grid so that the agent always seem to go North, and finally extract indicator features for the relative positions of other snakes and candies.

We first modeled Q as a linear function of such features and got surprisingly good results. Using indicator features is a common trick in reinforcement learning, because you can (almost) train as much as you want (so you don’t really have to care about the feature space size and overfitting) and linear functions become very expressive. However this obvioulsy still have some limitations so I later decided to experiment with neural nets. I tried different simple architectures and got the best results with a single hidden layer and ~ 20 units.

The neural net model performed a lot better than the linear one. As described in the report the linear model was easily able to beat a depth-2 Minimax agent (ie which looks 2 steps ahead) when trained against it, but had trouble beating a depth-4 Minimax agent (even when trained against it). However when fitting Q with the simple neural net and training the agent against a depth-2 Minimax, the RL agent easily beat depth-4 and depth-5 Minimax agents (Minimax got average scores around 75, while the RL agent reached scores of 95-100).

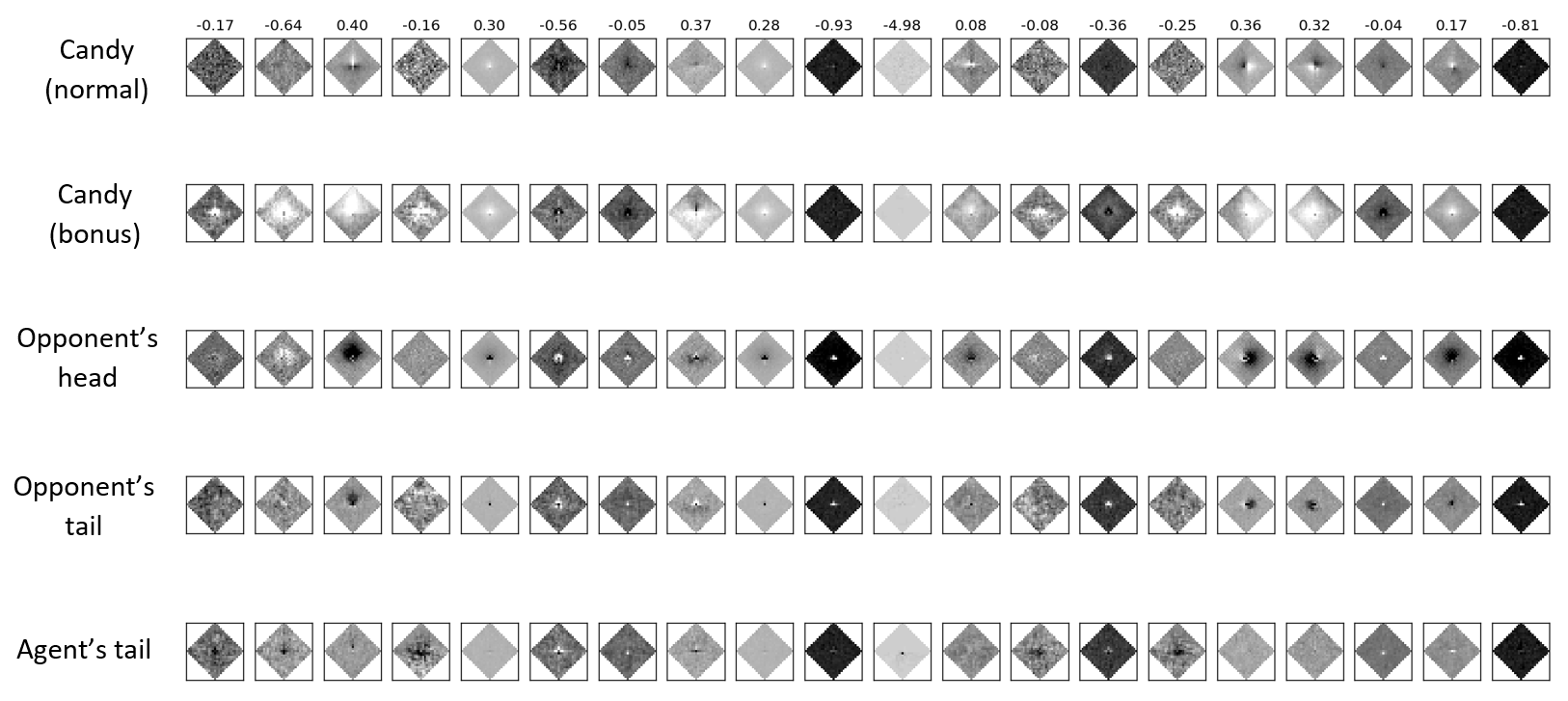

The weights of the best neural net are displayed on the figure below. Each column corresponds to a different neuron and each line corresponds to a different group of features. The center of the diamond corresponds to the position of the agent’s head, and higher weights are in white. For example, we see that the 3rd neuron has high positive weights for candies in front of itself but negative weights for opponents at these positions. It is interesting to look at neurons 16 and 17: these are measuring the quality of respectively the right and left sides of the agent, something that we instinctively thought would matter. In comparison, a linear model is not able to distinguish between candies on the right side and opponents on the left side, but can only sum everything up.

Conclusion

This project was a lot of fun, and there’s still a lot that can be done. Feel free to reach out if you’d like to expand our work or have any question!

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]